Before there was Hope in the Dark, there was Laughter in the Dark.

By that, I mean dark humour, black comedy, a grunt from the gallows. Some trace this kind of sniggering back to the Ancient Greeks, but no doubt, it goes further still. Yet ‘black humour’ as a term wasn’t coined until 1935, when André Breton compiled an anthology of writing on the subject.

It’s a comic style that pokes the taboo and then gurns in its face. There is provocation, discomfort, even a shiver of fear. You wince as you chuckle; maybe you feel ashamed for laughing. That makes you laugh harder, but with a little faint groan. You admire the audacity. The sheer brazen balls of it.

To me, black humour is a peek into the darkest corners of your mind to drag them out into the open. After all, what is a laugh but a sharp doubling into yourself, like you’ve just been kicked in the solar plexus? A black laugh swipes away all the dross, all the tittle-tattle, the pretence and the pleasantries. Holding up the world to the light can make you laugh at the terrible, disgusting truth in the glint.

I call my own book, Another Justified Sinner, a black comedy, but who really knows? Still, as I wrote it, I found myself smiling that wry smile that comes with holding the dark in your grasp. So, to celebrate that feeling, let’s look at five books that made me laugh and want to throw up all at once. Five books very dear to me, and now more than ever…

Five black books

1. Slaughterhouse-Five by Kurt Vonnegut

1. Slaughterhouse-Five by Kurt Vonnegut

The devastation of Dresden is even more gruesome for Billy’s resigned, deadpan look at the course of human history: ‘So it goes’. And never has irony been better served as a side-dish to meaninglessness.

2. The Joke by Milan Kundera

2. The Joke by Milan Kundera

I could have chosen any of Kundera’s books, really (they’re all so ridiculously, fantastically flamboyant), but I’ll settle for this farce about a joke that goes wrong. Kundera loves to highlight the absurdity of humans and the illusions behind our conduct. The horror and holler of a self-aware grimace.

3. Geek Love by Katherine Dunn

3. Geek Love by Katherine Dunn

This story of a travelling freak show feels wrong and revolting, yet always engrossing and with a softness to the core. It celebrates difference by really showing that difference, with no holds barred.

4. When the Professor Got Stuck in the Snow by Dan Rhodes

4. When the Professor Got Stuck in the Snow by Dan Rhodes

Dan Rhodes is an acquired taste but I find him compulsively readable. This one rips into a ‘fictional’ Richard Dawkins, who ends up lodging with a vicar and dissecting a puppy in front of schoolchildren to demonstrate his intellectual position. It’s delectable satire that always goes too far but always has a point to make (in this case, the fallacy of absolute knowledge).

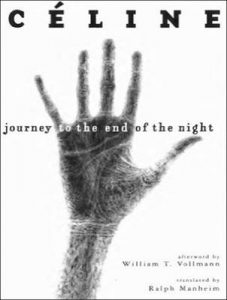

5. Journey to the End of the Night by Louis-Ferdinand Celine

5. Journey to the End of the Night by Louis-Ferdinand Celine

The tale of antihero Ferdinand Bardamu, caught up in the monstrosities of World War I and life beyond. There is a savage, sarcastic humour and an outlandish style that knocks you about the head until you gasp for release. This is a man angry at the idiocy of society, and with every right.

There you go, but oh, there are so many others (American Psycho, Trainspotting, Catch 22, or the more gently grim titter of Against Nature or The Bottle Factory Outing) – too many to list. I’d love to hear your own suggestions (@hopesmithery).

But, in the meantime, let’s dig deeper – why do we need such books at all?

How to starve a fever

These days, the whole world seems to be ‘a comedy of terrors’. Transcripts of Trump read like ready-made satire. We don’t even have to supply the punchlines.

There’s a danger that humour can make something awful seem normal and harmless when it most definitely isn’t. But I think, in a way, that is its greatest power: knocking people and concepts off pedestals, so the trance is lifted.

In 2016, in The Irish Times, author Lisa McInerney wrote: ‘When things are stressful or frightening, people develop thick skin and an appreciation for the absurd, for gallows humour… We poke at the Reaper.’ She went on to add that, in the right hands, this kind of joke is ‘teasing out a reader’s complicity in monstrous acts’.

And when I read this, I thought “Yes! ‘Complicity’!” It’s seeing the monsters we all have inside us, our beasts and our burdens – and when we laugh at the world, we all bare our teeth.

That’s monstrous, yes, but it is also defiant. For this kind of complicity and knowingness soon moves us to the next stage: now we know our part, we must play our part.

To laugh in the face of despair is a show of strength; an act of rebellion.

In the book Surrealism: Key Concepts, Michael Richardson writes: ‘If… black humour may be powerless to act against the sickness at the height of the fever, it can function as a preventative measure against its manifestation in the first place… [It’s] not so much a sign of madness as an indication that one has recognized the madness of the world, and even one’s own collusion with it’.

We laugh in order to recognise; to recognise and resist.

Sophie Hopesmith is a 2012 Atty Awards finalist and her background is in feature writing. Born and bred in London, she works for a reading charity. She likes comedy, poetry, writing music, and Oxford commas. All of her favourite films were made in the 70s.

Her debut novel, Another Justified Sinner, is crowdfunding on the Dead Ink site now.