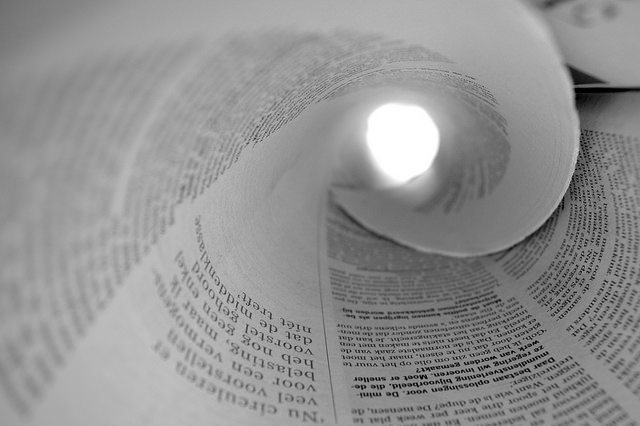

We are all detectives. Every day, we question the world around us, search for meaning, and seek to uncover hidden truths about life and ourselves. I think that’s why the genre is so enduring. There’s something fundamentally human about asking questions and trying to unravel the mysteries we’re faced with. Every time we open a book and begin to read, we’re playing detective, whether it’s a crime story or not. Every reader is a detective, searching through the author’s words for clues, trying to piece together the literary puzzle, and discover the meaning locked within the text. Reading isn’t passive, it’s active. That’s why we don’t like being told what happens; we want to figure it out for ourselves.

Fictional detectives go all the way back to Edgar Allan Poe’s Auguste Dupin, with a lineage and history that includes the work of Arthur Conan Doyle, Agatha Christie, G.K Chesterton, Dashiell Hammett, Raymond Chandler, and many others, along with writers who began to experiment with the genre like Jorge Luis Borges and Alain Robbe-Grillet (alongside a couple of the names on my list below). However, there’s an argument to say that the detective story goes back to classical mythology and much further still. Are all stories not ultimately about the search for truth? One of the things I like most about detectives is that they don’t blindly accept what they are presented with. And in the so-called “post-truth” era that we currently live in, I think it’s more important than ever that we all do the same and question the world at every opportunity.

It’s probably for that reason that I find myself drawn, not to gun-toting police officers or enforcers of the law, but to a different kind of detective – the cerebral, literary, often slightly odd characters who see the world in a unique way and who take on the role accidentally after finding themselves at the centre of a mystery without realising it. These alternate, accidental detectives are my kind of characters and here are five of my favourite examples from books and films:

***

The New York Trilogy by Paul Auster

If you’re talking about metaphysical detective fiction then there is no better example than the book which established Paul Auster as a literary star in the 1980s. Auster didn’t invent this genre, but, in my opinion, he perfected it. His trilogy, containing three, short interconnected novels, City of Glass, Ghosts and The Locked Room, combine to create a masterpiece of beautifully cool prose, pitched somewhere between Beckett’s sparse use of language and Chandler’s hard-boiled rhythm: complex, philosophical ideas made accessible and engaging and fascinating literary allusions and references. Auster subverts the conventions of the detective genre to ask questions about being and knowing, the nature of truth and language, and the relationship between the self and reality, such as what, if anything, can we ever really know with any certainty? At the same time, he’s playing a game with knowledgeable readers of detective fiction by turning their expectations against them. In Auster’s trilogy, detective, author and reader literally change roles throughout. The first in the trilogy, City of Glass, is my personal favourite and features a protagonist who most closely resembles my model of the accidental detective. In City of Glass, a writer of mystery novels who is withdrawn after the death of his wife and son accidentally intercepts a phone call intended for a private eye and decides to take on the case himself. If you enjoy detective fiction and you’ve never read Auster – this year nominated for the Man Booker Prize for 4, 3, 2, 1, then this is the perfect place to start.

Molloy by Samuel Beckett

Jacques Moran is a decidedly unusual private detective who is charged with the task of locating a man named Molloy. However, he’s not entirely sure what he needs to do once he’s found him. Moran’s narrative take place in the second half of the novel Molloy, the first in Samuel Beckett’s trilogy of interconnected novels, Molloy, Malone Dies and The Unnameable, which were written in French between 1946 and 1950. The detective, Moran, and the man he is pursuing, Molloy, are two sides of a Moebius strip, with the former gradually collapsing into the latter. In this strange, circular novel that’s somehow both skeletal and dense at the same time, Beckett, who was reportedly an avid reader of detective fiction in his leisure time, brilliantly anticipated the way postmodern writers would deconstruct the genre’s convention. Some 30 years before Auster would write his trilogy, Beckett was making the same epistemological enquiries and experimenting with a looping narrative structure that’s not unlike David Lynch’s Mulholland Drive or Lost Highway. The next two books in the trilogy, Malone Dies and The Unnameable, continue to explore Beckett’s interest in the relationship between author and character, creator and created, as he strips back his language further and further, in the search for the unreachable core of the self. Maybe follow this with something a bit lighter… like The Silence of the Lambs.

The Crying of Lot 49 of Thomas Pynchon

Oepida Maas is a Californian housewife who is drawn into a bizarre and labyrinthine conspiracy, seemingly involving the sinister and shadowy Tristero organisation and a centuries old conflict between two rival mail companies (which may or may not exist), after her wealthy former lover names her as co-executor of his estate following his untimely death. Pynchon’s novella, filled with strange characters (Oepida’s therapist turns out to be a Nazi hiding out since WW2) and dense with complex ideas and literary references (not to mention satiric flourishes and parodies of pop culture), is a hugely intelligent, magical mystery tour through a postmodern vision of 1960s America where nothing is what it seems. I could also have chosen the excellent Inherent Vice, one of Pynchon’s later novels, which was adapted into a film starring Joaquin Phoenix as private eye Doc Sportello who becomes embroiled in an equally strange and tangled conspiracy. Both books are at the most accessible end of the Pynchon spectrum yet remaining incredibly clever, postmodern novels.

Blade Runner (Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep by Philip K Dick)

Many of Philip K Dick’s characters find themselves playing detectives, often in their own lives, questioning the reality of the world around them and even their own identities and memories, but Rick Deckard is one of his most famous creations, largely thanks to Ridley Scott’s seminal film adaptation. Deckard has a touch of Chandler’s world-weary knight errant Philip Marlowe about him, but he’s also more of an assassin or executioner than a detective in many ways, particularly in Scott’s movie. He does, of course, undertake some interesting detective work along the way, and his conflicted, essentially good, nature ensures we remain engaged with him as a character. It also doesn’t hurt that Deckard is played by Harrison Ford who brings a real humanity to the role and has such a classic look in that dirty brown trench coat, with his hair cropped short, and his futuristic, modified handgun, that he’s simply too iconic to dislike. The ambiguity over his own status as human or replicant further adds to the intrigue. Scott’s dystopian noir is, in my opinion, one of the most visually beautiful, hypnotic and fully realised worlds ever committed to film. Philip K Dick is a genius of ideas and this is one of his greatest concepts. The novel, although very different to the film, is also excellent and I highly recommend many of his other novels and short stories, many of which feature characters asking the fundamental question of “what is real?” and “can we ever be sure of anything?”. We Can Remember It for You Wholesale (the basis for Total Recall) is another of my favourite PKD stories.

The Big Lebowski by The Coen Brothers

The Dude just wants his rug back. The man otherwise known as Jeffrey Lebowski has his rug urinated on and stolen in a case of mistaken identity which leads him into a noir mystery and kidnapping plot that’s straight out of the pages of Raymond Chandler, Dashiell Hammett and Ross MacDonald. However, the Dude isn’t a detective and he doesn’t want to solve a crime, he’s a dedicated pot-smoking, White-Russian-drinking bowler who wants his rug back, for the sole and simple reason, that it “really tied the room together”. The Coen brothers’ cult classic is one of the most profoundly funny, absurd, clever and deeply brilliant movies of the last 30 years. The script is sublime and the performances – particularly Jeff Bridges, John Goodman and the late Philip Seymour Hoffman (although the entire cast is amazing) – are beyond perfection.

***

These are five of my favourite alternate detective stories, but I could have easily made this a “Top 20” list if I had the time and space. I have so many favourites and I’m sure you will have your own suggestions too. I’d love to hear them @danjameswriter. These aren’t necessarily my favourite detective characters, but I think they fit together well as a list. As I said, I could go on and on, and I’d love to have included a couple of other books such as Alan Moore’s masterpiece Watchmen, Flann O’Brien’s surreal and brilliant The Third Policeman and the mind-bending short stories of Jorge Luis Borges.

Before I close this case file, however, I will mention a few more of my favourites, including one or two more traditional detectives who I couldn’t include on the list above for various reasons. Special Agent Dale Cooper returned to our screens recently in the sublime Twin Peaks. He’s a great character and definitely a favourite of mine. In his original incarnation, he was full of boyish enthusiasm and wonder, coupled with a belief in dreams and intuition (the Tibetan method), while more recently he’s been a kind of idiot savant in the vein of Peter Sellars’ character Chance from the film Being There. Either way, I could watch him all day. Rust Cohle from the first season of True Detective is another superb TV detective. His bleak yet incendiary monologues about the nature of existence are enough to put him on anyone’s list of favourite detectives. In books, you’ve got the great Dave Robicheaux from James Lee Burke’s wonderful series of poetic, lyrical and brutal crime thrillers set in New Orleans, and there’s also Hieronymus “Harry” Bosch, the compelling and streetwise cop from Michael Connolly’s LA-based series. True, the latter are more straightforward detectives, but they’re two of the very best examples of crime fiction that I’ve read. Finally, there’s Raymond Chandler’s private eye Philip Marlowe, whose adventures I will never tire of coming back to.

There is one detective still to mention of course, and that’s me. In my debut novel, I tell the story of how, as a journalist and biographer, I found myself investigating the life of a reclusive artist who had disappeared without a trace, and taking on the role of detective to uncover the truth. Like my favourite five above, I don’t know much about police procedure or shoot-outs, but I’m cerebral, literary and a little different, and when it came to the mystery of Ezra Maas, that’s exactly what was needed to navigate a world of fractured identities and sinister doubles, where fiction and reality had become dangerously blurred.

The thing about playing detective is, it can become an addiction. Once you’ve started pulling at that thread, once you’ve crept down into the basement and shone a light into the dark corners, once you’ve started questioning the world around you, there’s no turning back. But you know what? That’s a good thing. We live in a world that can’t be trusted, where newspapers and television broadcasts, even the leaders we elect, can tell us something is true when we know for a fact it isn’t, where propaganda is portrayed as fact and facts are dismissed as fake news. My advice? Don’t accept what you see. Don’t believe what you’re told. Listen to your intuition. Trust the voices in your head. Play detective.